If your subscription uses a freemium model, it can be tricky to decide what’s always free, what’s free for a while, and what’s always behind the paywall. Knowing how to manage people at each stage of the funnel can be really challenging.

Today’s guest, Ken Houseman, is an expert on both the strategy and the technology required to monetize the funnel for acquisition, upsell, and retention. Today’s conversation isn’t based purely on Ken’s work as VP of Product for The New York Times, and in no way represents the editorial perspective of the organization. Ken’s experience there, as well as his work with organizations, including Oracle, Nike, and even the US military, have shaped his perspective on managing the customer relationship.

In this conversation, we discuss why retention is the next obsession for subscription leaders, what needs to be different about how to optimize your ERP for subscriptions, and a few of the less obvious things that can go wrong on the path to conversion.

—

Listen to the podcast here

Best Practices in Subscription Funnel Management, with Ken Houseman of The New York Times

If your subscription uses a freemium model, it can be tricky to decide what’s always free, what’s free for a while, and what’s always behind the paywall. Knowing how to manage people at each stage of the funnel can be really challenging.

Today’s guest, Ken Houseman, is an expert on both the strategy and the technology required to monetize the funnel for acquisition, upsell, and retention. Today’s conversation isn’t based purely on Ken’s work as VP of Product for The New York Times, and in no way represents the editorial perspective of the organization. Ken’s experience there, as well as his work with organizations, including Oracle, Nike, and even the US military, have shaped his perspective on managing the customer relationship.

In this conversation, we discuss why retention is the next obsession for subscription leaders, what needs to be different about how to optimize your ERP for subscriptions, and a few of the less obvious things that can go wrong on the path to conversion.

—

Robbie Baxter: Ken, welcome to the show.

Ken Houseman: Hi, Robbie! I’m really glad that we were finally able to make this happen. I’m excited to have the conversation today.

Robbie Baxter: Me, too! Well, let’s jump right in. Can you explain what your job is at The New York Times? What are you responsible for? And what are the kinds of questions and decisions that you’re making on a regular basis?

Ken Houseman: I get this question a lot from family and friends. What exactly do you do because you’re not a journalist? It’s sometimes a hard question to answer. But as a product strategist in general, the one thing that I tell people is my job is to make sure that I understand the strategy and direction of the company, and that I put mechanisms in place that move us towards a safe and compliant manner. But I’m also responsible for making sure that as we go through that growth process, we are opening more doors for the future than we’re closing. And so as a product strategist, particularly in commerce, I have to balance the quick win versus the core platform thing that’s going to make sure we have flexibility in the future.

I’ll give you a good example of that. When you go through a hyper-growth period with a subscription business, you’re not always thinking about the funnel, right? You may just have natural growth that’s happening because you’re new on the market. And so, as you’re trying to capture as much of that paid acquisition as possible, you may not be thinking about how free trials interact with your core subscription and billing system or whether or not you want to start doing gift offers or pay on behalf or shifting to a usage model instead of a monthly or weekly subscription, and if you don’t think about those things years in advance, you build yourself into a corner, and then pivoting to take advantage of those business options can take years to undo.

Robbie Baxter: The New York Times is quite sophisticated and quite far along, as you said. Newspapers were among the early adopters of subscriptions. So these are questions that I think The New York Times has been thinking about and eventualities. You’re bringing them onto a technology platform. But these are bundles and trials, annual versus monthly versus weekly versus other ways of paying. Those are questions that when you came into the role, were things that had already been wondered about. Pretty sophisticated organization.

What advice would you have for somebody who’s just starting to run a product team in a subscription where their model is still pretty simple? Let’s say one offer, one trial, and nothing else. I think a big challenge that a lot of practitioners face that are in the product role is how much do I plan for the future? How much do I just try to optimize for right now because who can know what the future holds?

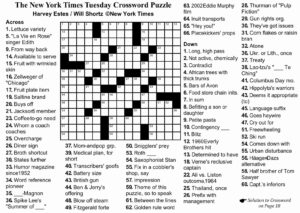

Ken Houseman: Yeah, it starts with making sure you deeply understand as a company, “what is your value proposition like?” What are the things that differentiate you in this growing multitrillion-dollar subscription industry? Are you a commodity? Do you have a product that no one else has? Do you have technology? Is it a particular process? Is it an access model? Whatever that is indexed on that being the thing that you spend your highly expensive engineering technical resources doing it better than anyone else in the market. Because that’s your bread and butter, and that’s the thing that is going to make sure that you constantly win, regardless of the changes in the economic environment. Everything else, try to find the best partner possible to put it on autopilot. I use an Axiom all the time that no one in their right mind goes to their friend and says, “Robbie, you have to buy a subscription to The New York Times, because they process my credit card like nobody’s business.” But the minute I get that credit card processing wrong they will go to you and say, “Robbie, don’t bother, go to the Washington Post or go to the Seattle Times,” and so we have to make sure that we are sort of out of sight, out of mind, and frictionless from those experiences, because that’s our real money maker is the quality of our journalism, the engagement with all of our other products across the bundle. There are those times that maybe you’re saturated on journalism, like some of our customers, you read it page to page. Then what do you do with the rest of your day? You know you play the spelling bee. You do some cooking, then you learn about an ingredient, and then you search that there was an article about that a while back, and then all of a sudden, it shows up in the crossword puzzle. It’s that type of thinking–we want to focus there. We don’t want to focus on reinventing billing systems and credit card processing.

The New York Times Crossword Puzzle: Beyond journalism, explore spelling bees, cooking, and hidden connections. Our focus is on creativity, not reinventing billing systems.

Robbie Baxter: If it’s not an area of differentiation, find a partner if you can, and make sure that the box is fully checked. I think that was your added comment. So that it’s a non-issue. It’s friction-free, and then invest in what differentiates you. In your case, content.

Ken Houseman: Yes, and I think that hits it on the head. And then I would just say, Don’t underestimate the need for quality data. Any partner that you partner with and any system that you build internally, data data data, you have to understand the behaviors of your subscribers.

Don't underestimate the need for quality data. Share on XEvery time you experiment and introduce anything new to that experience, you need to measure and know how it’s impacting your core KPIs so that you can constantly groom that experience.

Robbie Baxter: Yeah. I’ve heard you say retention is the next obsession. What does that mean? And how does that tie in with data?

Ken Houseman: In my opinion, when it comes to retention, if you launch a product and someone starts using it and you just let it sit there, people go through different times of their lives. Maybe they get bored or they hit economic hard times, and so they have to prioritize the things that they’re paying for. Retention is about making sure that, first of all, you are constantly finding those natural connections with your subscribers for what matters to them in your product and making sure that it’s at the front of their mind. As for me, I’m a weekend baker, so when I get the cooking newsletter throughout the week, I’m thinking about, like, “Oh, that’s a recipe.” I save that one, and going to the weekend, and now I’m cooking. That keeps me engaged in that product. But for someone else, they may not want to cook at all. And they might just be like hyper-political consumer so they want all the political news, and so not just making sure that they have clean access to the journalism, but making sure that we have strong personalization that allows them to serve up that the political news to the top of their news feed and so finding those different ways of making sure that we’re front of mine, naturally connecting with those subscribers is important, and the only way we can do that is to know what you like, and the only way we know what you like is managing your preferences, understanding what things you click on, how often you’re in each of our products, and then using those behaviors to say like, “Hey. There’s this other thing over here that maybe you didn’t know about. And we think you’re really going to like that based on the data that we have.” It’s tricky because you don’t want to be creepy. But you do want to be relevant and timely. I think that also feeds them into pricing discussions. One of the fastest ways to lose a subscriber is to price them out. And so when you’re thinking about your upgrades to bundles or your cross cells, make sure that you have a price point that really not just entice them to get in but matches the value at that time in their life cycle.

Retention is about making sure that you are constantly finding those natural connections with your subscribers for what matters to them in your product. Share on XSo one of our offers, we have a $1 a week intro offer as a new subscriber to the bundle that’s perfectly priced for you. It’s a low barrier to entry. Maybe you’re not familiar with all of our products. It’s relatively low cost, but over time, as you get experience and may engage, you understand the full power of all of our products together. And we understand your behavior. Now, we can start to analyze, like how much of our product are you using? When we step you up to full price or a discounted full price, how do we understand what you’re willing to pay for the things that you do care about?

One of the fastest ways to lose a subscriber is to price them out. Share on XRobbie Baxter: We’ve talked before about funnel management. And I think you’re really good at this. When you think about funnel management, for a lot of organizations, the funnel stops at the moment when the person signs up, but it sounds like you have a broader perspective on how long the funnel lasts or how long you’re responsible for managing that funnel.

Ken Houseman: Yeah, it’s interesting, particularly in journalism, news, and media. Because we have a really broad footprint that generates a funnel for us. You see The New York Times sitting on the newsstand at your local bodega. Regardless of how you feel about the brand. Everyone in America knows The New York Times. And so because of that, we have a pretty wide market potential and funnel.

I think when you search “news”, often our brand comes to the top of the Google search. There are lots of things that for public policy, like we will make certain things, like our COVID tracker, free to the public, and that naturally generates traffic to the website. And so, from that point, we have a really wide brand of the funnel.

Now, most subscription businesses, particularly when they’re first starting off, they have a hard paywall. You have either no access, and then you pay, and you have access, or you have a very minuscule amount of access. Then you pay to get the rest. The only way to really soften that sort of abrupt wall and move from a wall to more of a flow, is to start experimenting with things like free trials that sort of get them behind the paywall and experience the product. But for us and in the world and the future world of data and machine learning, it’s all about understanding your behaviors and what you’re tracking so that we know when is the right time to put the paywall in front of you. It’s not based on any particular number or set of behaviors. It’s really like, what are you ready for? And then we have offers discounted at a range of potential offers, everything from individual products to our full bundle. And based on your behaviors again, we match that like when to create the throttle and the paywall, with what’s the right offer and price point to put in front of you. That’s the real magic sauce. Because even if you don’t take advantage of it, then that feeds back into our model, and we know that you didn’t take advantage of that one. And so then we use that to train and make sure that we understand why you didn’t take advantage of that. And so that the next time we put it in front of you we are doing it at a time and at a rate that we know you agree with us that our journalism is worth paying for.

Robbie Baxter: Let’s say, you use the best information you have through your machine learning-based algorithm. We put an offer in front of me, I don’t take it. It was the best time that you could imagine for me to look at it. But it didn’t work. That information gets fed back in. Do you actually look at that as a person? Or do you kind of just trust that the algorithm will figure it out, or do you say, “Wow, this is funny. People who look like Robbie for some reason, aren’t signing up, even though everything in our experience would tell us that this is the perfect time for us,” How do you think about that? Especially in this age of AI and generative AI. Where’s the human component?

Ken Houseman: AI is a tool. Spreadsheets were a tool. Databases were a tool. AI and machine learning. It’s just a tool and at the end of the day, if you believe that you’re going to set it and forget it, I think you are headed for making a really big mistake. Because the model may not change but the environment changes. People who look like Robbie, but you know there may be a subsection of people who look like Robbie who are in a slightly different age demographic, or gender identity, whatever those different things are, or people who look like Robbie, who lives in San Francisco may not be the same behaviors of people who look like Robbie, who used to live in San Francisco but now they live in New York.

When you find that there are behaviors that aren’t meeting your experiment expectations. That’s when you, the human factor, come in and you have to dig deep to understand why, and when you understand why, then you can retrain those models and target in a different way.

Innovation in Action: Constantly measure and optimize the impact of new elements on your core KPIs to refine and enhance the overall experience.

Robbie Baxter: Yeah, that’s great. I love that because I think what’s important for people to understand is that whether you have sophisticated systems or you’re relying on your best guess. A lot of it is hypothesis-driven. You look at whatever data you have. And you say, what is it about this group that’s different? That might explain why they’re not behaving as we would have predicted.

Ken Houseman: Looking beyond, just really coming up with all kinds of different reasons why. One, Robbie might not take advantage of that offer at that moment in time, because the price was a little too high and not willing to pay that right now. Sarah might look at that same offer and say, “I would buy that. But I’m not going to click on it like the price is fine, but I’ve got 7 other subscriptions right now. I just don’t need another one. Joseph might look at it and say, “Oh, this is really great. But I’m on my phone in transit right now so I’ll come back to this later.” Those are all very distinctly different reasons why those people didn’t take advantage of your offer, and you have to understand that so that you can tailor the experience the next time.

Robbie Baxter: Right. That’s so important. I’m just thinking about organizations that might say, “Well, I can’t do that because we’re not as big or we’re not this or that,” but you can think with each of those examples, Robbie, Sarah, and Joseph. Right? Robbie says, “I don’t see enough value in it.” If you have a hypothesis, that’s the issue. Maybe we don’t have enough value. Then you can experiment with putting, a lower price or more value. If it’s the Sarah example where it’s like, I have too much already. I’m overwhelmed already. Then you might say, “This is the best one,” and you might have a pitch that talks about letting go of some and having this to be for others, or maybe bundling. And for Joseph, you might want to just track when he does buy. Try to understand what he’s seen before, and what was the last thing he saw before he made the decision. Very different kinds of actions and it’s great if you have the data that proves it. But even if you’re just guessing, you can put experiments in front of people that might give you a better sense of what’s really going on.

Ken Houseman: Yeah, I think it also helps you prioritize. Especially as a nitty-gritty startup you really have to be proactive of where you focus and the limited resources that you have. And if you understand those different areas, then you can go say, “Oh, based on this data criteria, how many people fall into each one of these buckets that we’ve seen over the past 3 months? 6 months?” That helps guide you on which one is worth the experiment because that will tell you which one has the highest population that might convert instead of trying to tackle everything it wants.

Robbie Baxter: Yeah, so looking for big segments is important to understanding who fits the profile. I had a conversation this morning with a client, and we were talking about this, and they’re very mission-driven. And they said, “We aim to serve everybody.” Like, everybody does, we have a limited budget. I said, “Okay, which segment do we want to focus on today?” At some point, we serve everyone perfectly well. But today, where do we want to start? And I think “big segment willing to pay”, “underserved segment”. That’s a good place to start.

Ken Houseman: Yeah. The more crisp that you get with that mission, and knowing that you can’t serve everyone. The others will come along but who’s your priority?

Robbie Baxter: I found it is so hard for organizations, founders, marketers, product people to say it’s not for everyone yet or it’s better for some people. We’re optimized for people who like to bake and care about politics, and enjoy puzzles. Those are that we’ve solved pretty well for that person. There’s a lot of them.

I want to talk to you about bundles, and thinking about how to bundle, when to present bundles, and when to expand the relationship over time with a customer, how do you determine kind of where to put where to put more into the offering and connecting the different product funnels to optimize for that?

Ken Houseman: I think this is a hard question when you have a really large product portfolio, which combinations of bundles do you want? Or in some hardware companies in the B2B space, it’s an endless combination. It’s not simple to order. Here’s the 5,000 parts that we have and the different connections they have with each other, and you can just pick and choose and couple it together and ship. For a business like ours, we really focus on making sure that if you’re only interested in one product, we want that to be the best product for you, priced for you. But if you’re interested in that product and one other thing, we’d rather go from that one product to the bundle. And we want to entice you to go to the full bundle at a price point that makes sense, knowing that you are going to be most likely to use the one thing that’s of interest to you. And sometimes the second thing.

Robbie Baxter: Clarifying question from one to the bundle. I like one thing, you charge me for one thing. I like 2 things, you go to the bundle. The bundle is more than 2 things. Is that what you’re saying?

Ken Houseman: Yes. For us, there’s the core journalism that’s the center of everything we do. We have cooking, games, the wire cutter, the athletic, and you can buy each one of those on their own subscription. You can buy all of them, each individually on your subscription. You can buy one directly from us and another one from Apple. We would never stop customers from doing that if that’s their choice, and that is perfectly reasonable.

But we truly believe that the power of The New York Times is in all of those things working together. And so if you become interested in more than just games, we don’t want to create endless combinations of games plus wire cutter games plus news games plus the athletic. We want to make it easy for you to say, “Hey, I like more than games. I want the bundle.” Because once we have you in the bundle that gives us the ability to understand your behaviors better and say “You know what I think you actually would like the athletic. Let me put this athletic article in front of you and see if it resonates. If it doesn’t, no harm. We’ll look for something else in our bundle to serve up to you. But if it does, great, let me take you deeper into that other part of the bundle, and make sure that you’re getting all the possible value from the entire bundle.”

The New York Times Cooking Section: At The New York Times, our core journalism is at the heart of it all. Whether you crave cooking, games, The Wirecutter, or The Athletic, choose what you love with individual subscriptions or bundle them all. Your choices, your freedom, because we believe in delivering journalism your way.

Robbie Baxter: You gave a great example of that in the hardware world. Everything is built to ship, and it’s highly configurable and highly complex. You’re saying we’ve deliberately chosen a much simpler way. Right? You come in, your point of entry is any one of our offerings, and then option two is not quite the same thing for everyone but it’s the bundle, right? It’s wherever you come in option. Option one is one thing, option two is everything. When does that make sense? Do you have a thought on when that makes sense versus when every person can configure their own package?

Ken Houseman: Yeah, that’s a really tough question. I think when it makes the most sense is first understanding that all of your products on your portfolio work together and that they have some sort of relationship with each other. So for us, when you look at the bundle, even though they are different distinct products inside the bundle, they all still feel like The New York Times. They all relate to each other, and so when you put them together in the bundle, it’s very natural.

But if you, if that natural connection isn’t there, maybe the bundle isn’t the right thing for you. If it’s very distinct experiences, distinct products or services that you’re delivering, maybe it is better to keep them separate and then offer discounting when you have both subscriptions.

Robbie Baxter: Yeah, because I guess that’s the other option, the more you buy, the more you save, right? If you sign up for two things, you get 10% off. Sign up for three things, you get 15% off. I’m making this up. It’s important. I think you’re right. If the full offering, if you can imagine the same subscriber getting value from all of them, and having it make logical sense that this would all come from the same provider. It’s a lot easier.

I also think, and I’m interested in your opinion on this, that when you have too many offers, it’s overwhelming for the consumer. Then they say, “It’s too much. I’ll come back later when I’m not so busy because there’s a lot to do. I have to be an expert on The New York Times pricing model, and I don’t have time to dig deep into that. So I’ll come back tomorrow.”

Ken Houseman: Yeah. I mean, the traditional way of addressing that is abandoned carts and following up with emails or messages to say, “Hey, I saw you were looking at XYZ. Don’t forget, or here’s a discount coupon to finish that transaction.” That is important, like saving that abandoned card or saving a stop from churn is super important. So I don’t want to marginalize that at all. But if that’s all you’re doing, that’s not enough, because what you should be obsessing about is that they never should have abandoned the cart in the first place, they never should have churned out in the first place. It is extremely more cost-effective to focus on that retention and the click-through sale than it is to figure out why they left and get them to come back, because once they’re out the door, it’s twice as hard to get them back into that flow.

It is extremely more cost-effective to focus on that retention and the click-through sale than it is to figure out why they left and get them to come back. Share on XRobbie Baxter: Yeah, there’s definitely a half-life on enthusiasm.

I think managing the funnel gets a lot harder when you’re limited to first-party data. I’m interested in your thoughts. We opened the conversation by talking a little bit about various regulators cracking down on privacy and personalization. What does that mean for a person whose job is to bring people through the funnel, often working with third parties, working with other organizations to try to recognize who’s going to be a good prospect, and what is the right thing to say to them at the right moment?

Ken Houseman: Yeah, you have to be voracious about seeking out what’s coming down the pipe. Anything that you can do to stay close to. If you’re international, all the different country regulations in the US. Every State has different laws that are applied. And you really just have to stay on top of it and try to understand which things are most likely to hit you. What I was talking about before, like which things have you built the flexibility that if they become a requirement, you’re ready to go, and you’re ready to pivot with relatively little effort, and which are the things that are like, “Oh, boy, if the Federal Trade Commission requires this, I have to completely revamp my entire landing page, acquisition flow, or cancellation.” Which is a big one right now in the US. Requiring equal ease to cancel online as it is to subscribe. That has really changed the way a lot of online cancel capabilities work across the industry. So you have to really look forward and then really ask yourself, “Am I ready for that if it happens, and how likely is it to happen?” And don’t get entrenched just because you had a path, a roadmap, and you had a strategy, the worst thing you can do is get super entrenched in that strategy such that you create a blind spot, and you’re not able to see what’s coming and realize that maybe it is, even though I’m like 80% there with what I’ve been working on. Maybe it is best to put that down and focus on this other thing before it becomes a real problem.

Robbie Baxter: Anticipating where consumer sentiment is and where regulators are focusing before the decision actually comes down.

Ken Houseman: Yeah, anything you can do to prep yourself and just stay nimble, stay flexible, and like a good football player on the field, practice that bouncing back and forth as often as you can because if you stay moving you’re a harder target to hit.

Robbie Baxter: I have a lot more questions, but I’ll say them for another time, and wondering if you have time for a quick speed round before we wrap up.

Ken Houseman: Sure, let’s do it! I love a good speed round.

Robbie Baxter: Okay. First subscription you ever had?

Ken Houseman: Oh, boy! I come from the era of cassette tapes by mail subscription, and so I used to get all of my music through Columbia House.

Robbie Baxter: Yeah, like the Hotel California. Favorite subscription you pay for today other than one of yours?

Ken Houseman: My favorite subscription that I pay for today, I would have to say is that I have a health app that I use. I won’t plug the brand, but I’m just a health nerd, and so it helps me. I value fitness. If I had to cut one subscription out of my wallet, that would not be it.

Robie Baxter: Okay, you were at Nike. What’s a Nike product do you love?

Ken Houseman: Oh, the Nike product I love? The Nike run app, just the analytics, the data, and the feedback around it. I’m not such a big runner anymore, but they really understand you, and they make it so easy to just keep running.

Robbie Baxter: I know you’ve lived in a lot of different places. Both in the US and around the world. A place where you’ve lived, where you enjoyed the work-life balance the most?

Ken Houseman: Oh, interesting! I think Japan. when I lived in Okinawa. When you were at work, you worked hard and people had high expectations, and then you just went and had a beer and some sushi afterward, and it was all good.

Robbie Baxter: That would be amazing.

My daughter just told me that she’s in one of her early career jobs. And she was saying, “Mom, there’s always more work to do like I never feel like I can completely check out. And I think I should be able to leave, clock out, get a beer, have some sushi, and not think about work until the next morning, maybe we need a little more of that.”

Ken Houseman: I’m ready for a beer anytime.

Robbie Baxter: Final question. An example of a subscription that you’re aware of today outside of news that you think does a really good job managing their funnel and where you kind of look at the experience as a consumer, and say, “Whoever’s on that one, they know what they’re doing.”

Ken Houseman: I think that the streaming media started to figure it out when they broke the cable subscription model. Everyone was really scrambling for what that would look like, and I think they figured it out now. Although they’re probably making more money now off of the seven individual streaming subscriptions that I have than with my one cable subscription, it’s all overhead for them. They don’t need to deliver all the channels that you’re not watching. They just delivered the one, and they’re making more money off of it.

Robbie Baxter: Yeah, it’s crazy. I have so many subscriptions. Ken, great to have you on the show. Thank you so much for stopping by Subscription Stories. I hope you’ll come back.

Ken Houseman: Absolutely, any time.

—

That was Ken Houseman, Vice President of Product for The New York Times. For more about Ken, follow him on LinkedIn. He posts frequently on all things product and revenue. And for more about Subscription Stories, as well as a transcript of my conversation with Ken, go to RobbieKellmanbaxter.com/Podcast.

Also, I have a favor to ask. If you like what you’ve heard, please take a minute to go over to Apple Podcasts or Apple iTunes and leave a review. Mention Ken in this episode if you especially enjoyed it. Reviews are how listeners find our podcast, and we appreciate each one.

Thanks for your support and thanks for listening to Subscription Stories.

Important Links

About Ken Houseman

Ken Houseman is currently the Vice President of Product at The New York Times, focused on their Subscription Commerce technology. He has over 20 years of experience in industries that span the U.S. Department of Defense, Semiconductor Manufacturing, Telecommunications Equipment, Cloud Computing, Footwear/Apparel and Media.

Ken Houseman is currently the Vice President of Product at The New York Times, focused on their Subscription Commerce technology. He has over 20 years of experience in industries that span the U.S. Department of Defense, Semiconductor Manufacturing, Telecommunications Equipment, Cloud Computing, Footwear/Apparel and Media.

Before coming to The New York Times, Ken worked at Nike in their finance technology organization and helped transform their Order to Cash systems as Nike pivoted further into their direct-to-consumer retail strategy.

He spent 2008-2016 at Oracle Corporation. There, he led various teams responsible for initiatives leveraging technology and scaling global operations. He’s led teams in large-scale ERP solutions and been the product lead in building out several enterprise solutions that helped Oracle adapt into the recurring subscription business that it is today.

Prior to corporate life, Ken spent 4 years in the military as an Air Traffic Control and National Weather Service Radar electronics engineer. He’s traveled the world and worked in over 25 different countries. He serves on various non-profit boards and spends his downtime looking for new global experiences.

Love the show? Subscribe, rate, review, and share!

Join the Subscription Stories Community today: