Everyone’s talking about “product-led growth” in the subscription world right now. Companies are seeing the connection between the way the product is designed and how effective the company is at acquiring, engaging and retaining customers—and even driving referrals.

To do product-led growth well, product managers need to think like business leaders, as well as thinking like product builders.

It isn’t easy and not everyone has the right skills. My guest today, Caitlin Roman, has led product teams at three great subscription-first organizations, LinkedIn, Medium and most recently The Athletic, which was acquired in January of 2022 by the New York Times, for about $550 Million.

I’m excited to talk to her, because she has developed pattern recognition about what it takes to build great products that actually help grow the business.

In today’s conversation, Caitlin and I talk about best practices learned at LinkedIn, Medium and The Athletic and the skills needed to drive product-led growth.

—

Listen to the podcast here

Product-Led Growth for Subscriptions, Using Examples from Medium, LinkedIn and The Athletic with Caitlin Roman

Everyone is talking about product-led growth in the subscription world right now. Companies are seeing the connection between the way a product is designed and how effective the company is at acquiring, engaging, and retaining customers, and even driving referrals. To do product-led growth well, product managers need to think like business leaders as well as thinking like product builders. It isn’t easy, and not everyone has the right skills.

My guest, Caitlin Roman, has led product teams at three great subscription-first organizations, LinkedIn, Medium, and The Athletic, which was acquired in January of 2022 by The New York Times for about $550 million. I’m excited to talk to her because she has developed pattern recognition about what it takes to build great products that help grow the business. In this conversation, Caitlin and I talk about best practices learned at LinkedIn, Medium, and The Athletic and the skills needed to drive product-led growth.

Welcome to the show, Caitlin.

It’s great to be here.

You’re an interesting guest for me because you’ve been at a number of different subscription businesses in various product roles. I’m wondering if you could share your subscription journey. How did you end up being a subscription product leader?

It was not a premeditated path, but it has been a fun journey. I love that subscription business models reward companies that consistently deliver value over time. It aligns these business incentives with customer needs. It’s been fun to get deep into that. My subscription journey started in 2015 after I graduated from business school and I came to work at LinkedIn. I had a choice of which business unit to work with, and I liked the premium subscriptions team.

I started in business operations, which gave me an in-depth look at the metrics of the business and how to operate a sub-business at scale. I then moved into product when the product manager I was working with at the time left. This wasn’t a premeditated move either, but as I started to get into product, it felt like a perfect fit.

Had you been a product manager before business school?

No, not at all. Honestly, when I graduated college, if you had told me, “You’re going to become a product manager,” I would’ve said, “What’s that?” I truly had no idea. Once I got into product at LinkedIn, it felt like a great fit for being able to bring people and teams together around this shared goal and figure out how to get there together. I’ve been in product ever since.

I know there are a lot of people who are either product managers or trying to become product managers. You found that it was a perfect fit for you. Why do you think product and subscription product was such a good fit for you?

Maybe we’ll talk about this a little more later, but I like being both in product to be able to think about customer needs, but also think about the business element of product. Getting to be in there at the ground level and see, when you think about a subscription business and how you’re acquiring customers, how does that translate into the technology? You set the strategy but then you also think about what the technological challenges are about something you may want to do, how you can work with engineering and design to problem solve together, and together make a decision that then, in turn, impacts the business. It’s this full-circle thing. To me, that’s really fun.

You came out of business school and came to LinkedIn, not as a product manager. Your boss who was a product manager left. You went into that role. You felt the ease of a comfortable shoe. What happened from there?

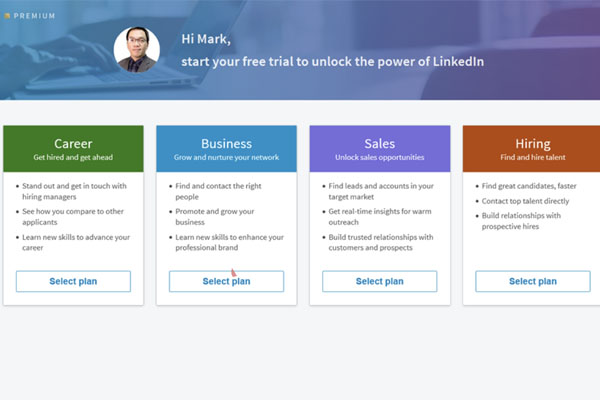

At LinkedIn, I was responsible for the acquisition of premium subscriptions. That’s the online lineup of subscriptions that LinkedIn sells across these four subscription families. It is a complex lineup. It is super interesting.

Those are four separate lineups. We had a guest a few weeks ago from LinkedIn who I think you know, Jill Raines. It’s a very big company with a lot of subscription depth. Can you name what those four categories are?

The first two are more consumer-oriented. Those are premium careers and premium businesses for job seekers and small businesses, respectively. You then have the online version of Sales Navigator, which is for salespeople. There is also this field sales component where there’s a more fully featured version that the enterprise team is selling. Similarly, for the recruiter subscription, there’s an online version and then there’s a field sales version. It is this mix of B2B, B2C, field sales, online across these four different subscription families.

That is highly complex. On the spectrum of subscription jobs, this is a pretty sophisticated organization when it comes to subscription variety and challenges.

I was enjoying my time at LinkedIn and was learning a lot there, but then, I got a call in mid-2017 from a friend who was at Medium. It sounded like an exciting opportunity to join a smaller company and be a part of that earlier stage growth journey. Being an online publishing platform, anyone can write on Medium. There’s this whole wealth of content in all sorts of categories from tech to personal stories on Medium.

Medium was launching a new product called Medium Membership, which is a paid subscription. At that point, there was no concept of exactly what the value proposition would be or what content exactly would be in the membership. I helped that business grow from its early days. I helped develop the paywall strategy and all of the growth flows there from the start, which is exciting. I started as an individual contributor PM. I built out a full growth product org there across four different product teams, which were acquisition, retention, payments, and SEO.

That was the org structure you chose. Was that the same org structure that you had experienced at LinkedIn, or did you develop that based on the unique attributes of Medium?

It was based on the way Medium operated and what our needs were. It evolved over time. I would say that was not the fixed structure from the beginning. We added one team. We split a team off and gave them their own charter. We then felt like it made sense to pull out another team. Payments came later on as we realized we needed to have more focus on that, especially since we were not only taking in payments for subscriptions but also paying writers. It has organically developed. That was me and my engineering partner. We developed that org structure together.

That is interesting.

After two and a half years at Medium, I left to join The Athletic, which is a sports media subscription business with coverage across all the major teams and leagues in the US and the UK. The Athletic was interested in leaning more into product-led growth for their already very successful subscription. I built that product growth team up there and did a lot of work around pricing and packaging.

A little over a year after I joined The Athletic, I became VP of product leading the whole product team. We were acquired by The New York Times in February 2022. The New York Times is perhaps the preeminent media subscription business. It was an exciting outcome for The Athletic and The New York Times. I decided to leave The Athletic after the acquisition closed in February 2022. My daughter was due to be born in March 2022 and I wanted to spend some more time with her. It’s been a whirlwind seven years in the world of subscriptions.

It is interesting. From my perspective, the structure and challenges of each of those roles are so different, but it also serves to give somebody a sense of the different flavors and range of possibilities in this category of subscription product or even general management of a subscription business. I wonder if you could briefly share your biggest learning in each of those roles. What did you take away?

They are each such different businesses at different stages, so it’s interesting to reflect back. With LinkedIn, what I learned is that how you acquire subscribers makes a huge difference in how those subscribers retain later on. We would run these experiments on what was called the chooser page, which was the page that lined up the four different subscriptions. We would change how we described those different subscriptions making even the smallest copy changes in who the subscription was for. That would impact conversion rates for the different subscription families.

You would see a month or two later that that would also impact the retention of those cohorts down the funnel. You could make someone think that they should buy a certain plan, but if it didn’t meet their needs, they wouldn’t stick around. This brought home to me that subscriptions are a long game. It pays to start out on the right foot with subscribers. Even if that means you might acquire slightly fewer at the start, you want to build that relationship with trust and with the right foundation from the beginning.

What about the other two organizations?

At Medium, what I learned is that the first action you prompt users to take when they reach your site matters. We had pretty big success asking logged-out users to sign up or sign in rather than asking them to subscribe and pay us as their first action. This goes back to the theme that is similar to LinkedIn about relationship building.

The first action you prompt users to take upon reaching your business website is extremely critical. - @caitlin_roman Share on XWhat is it that you’re asking users to do when you first meet them? You’re not saying, “Let’s get married,” but instead it is like, “Let’s go on a date. Let’s try it out.” You convince them to create an account with an email address, and that means you can reach them via email. You can send them great stories. They’ll eventually click on those stories. They’ll hit the paywall and eventually subscribe. It’s a journey. It’s not going straight to the end from the first click. That requires you to be a little patient and build great life-cycle flows as well to make this all work. We saw big success when we shifted the paradigm of what we were asking users at that first moment.

When you say you shifted the paradigm, what was the original paradigm, and then what was the later paradigm?

There were two flavors to this. One was simply when you reached the Medium site, we instituted a little popup that said, “Would you like to sign in?” It was optional. You could click out of it. Even asking someone, “Create an account. Sign in. Let us give you more personalized recommendations,” we saw big increases in logins and sign-ups from there.

The other piece was when we had our paywall, when you reached your limit, we said, “You cannot read anymore. Pay us.” Instead, we changed that for logged-out users to say, “Sign in. We’ll give you some more free stories,” and they could continue. Eventually, they would hit the paywall as a signed-in user, but we didn’t do as much of a hard blocking when someone was logged out.

Product-Led Growth: Convert more people into subscribers by telling them you have more free stories to provide instead of using a paywall to forbid them from reading further.

It was a more gradual approach and one that was more cognizant of the user’s journey to membership. At LinkedIn, you learned about the quality of the acquisition, the impact on lifetime customer value, and the ongoing relationship. At Medium, you learned about the importance of understanding that user’s journey to membership, and making that more of a gradual development, a dating period as you describe it, rather than just meeting someone and asking them to pay. In other words, that is like asking somebody you just met to get married. What was the main learning at The Athletic?

At The Athletic, it’s in that vein, but maybe even more macro. It’s that if you have real value behind your content, you can confidently charge for it. This is something that the industry has gone back and forth on. Can you get someone to pay? Does the subscription model work? Our journalists were incredible and the best in their field and we had a hard paywall. What The Athletic showed is that if the content you’re producing is so great, it works. People understood that the only way that they could access the content was to pay. That was a very clear message.

As you get bigger, you want to use different promotions to help people get more comfortable with taking out their credit cards. You got to work on growing top-of-funnel awareness and consideration. This idea that fundamentally you could build a subscription business with high-quality differentiated content was great learning for me of working on The Athletic, and feeling confident in the product that we were selling.

I love that. It is important and overlooked. One nuance I want to point out is that there is a lot of high-quality content that people are not willing to pay for. One of the things that’s important, and I’ve seen a lot of news organizations fail in this area, is that they say, “I had a smart journalist write a high-quality, well-researched, and well-supported story. We have high-quality content. Why aren’t people paying for it?”

It also matters whether this is content that people are willing to pay for. It requires a different lens than, is this content that someone will read? Is this content that someone will click on? There’s a different bar. For a lot of newsrooms, it requires a different way of thinking about what stories to write and how to write them.

That’s a great point. That is one thing. The category that The Athletic was in is sports. There is such a high willingness to pay there. That’s a great additional lens. It’s high-quality content and a category that is so desired. People’s passion is such that they are willing to pay. It’s a combination of those two things.

I did an early interview with Greg Piechota from the International News Media Association. We talked quite a bit about how a lot of news organizations are trying to figure out the difference between news that gets clicks and news that people are willing to pay for. For me, The Athletic has always been a good example of an organization that, from the beginning, knew they were focused on news people would pay for. Your point about people being willing to pay for sports news is important. Particularly, the well-researched, well-written, and timely sports news seems to me the life of a sports fan. There is a limitless appetite.

It’s true.

I wanted to circle back to something that you said. You were talking about product-led growth. I was wondering if you could explain what a growth-led product team is and how that differs from a normal product team.

As I’ve gone through these different roles, I’ve started to see that there is this differentiation between growth PMs and more of the core product org. That is in terms of how you think about setting up those teams, the surrounding functions, as well as the actual product managers, and the skillsets that you’re looking for in those different types of product teams. I don’t mean to say here that folks have to be one or the other. You can cross over between the two and be successful, but I have seen that the best growth PMs are in a slightly different mindset when they’re in that growth role.

The way I think of it is growth PM is sort of this GM, PM. GM means General Manager and then PM means Product Manager. You’re also helping run the business in addition to shipping products for users. That’s the key differentiation. Of course, core product managers may be looking at metrics around engagement and that sort of thing, but there’s still this extra layer when you’re truly in a growth situation where you have to understand the business model of the company, the growth strategy, and how those growth levers can be used to drive the business.

There’s also this layer where you have to help operate the business on a weekly basis. In my view, the best growth PMs will be doing this. You’re thinking about how the business performs, and how that compares week over week versus expectations. Especially if the company has a financial plan that you’re trying to hit, you want to be well-versed in what those expectations are and how you’re performing against the expectations. You may have to make adjustments to the product plans based on that performance.

It’s that full loop I described where you understand what’s going on in the business. You translate that with your engineers, designers, and analytics team into an experiment or a tweak to the product, and then see how that drives business outcomes. Being fully comfortable in all stages of that cycle is where growth product managers shine. You want growth PMs to have great user intuition and work well with engineers, but that business lens that you can add is so important.

Going back to your original story about how you started at LinkedIn more in a business role and moved to product and growth orientation and found your place, it is interesting. It’s not like a product manager is a product manager, is a product manager. Especially as a subscription business grows, there might be billing specialists and growth specialists. They certainly have different priorities. They might even have different personalities.

In the personality piece too, there is not just the skillset lens but there is also what your interest is. I found that some people like having revenue responsibility and accountability. They find it exciting, and other people find it stressful. You want somebody who has that interest in owning a P&L or being part of that P&L ownership in addition to simply having the business skills. It’s a little bit of a personality check if you’re thinking about going in it as well. Do you think that the level of revenue responsibility is something you’d like to have?

I want to change gears a little bit and talk about everybody’s favorite topic, which is pricing and packaging. How many tiers should you have? How should they be focused? Is it focused on volume and commitment, or is it by different profiles or personas? I know you had an interesting experience early on at LinkedIn that helped to form some of your perspectives on this. Could you talk a little bit about how you thought about the premium options circa 2016, what decisions you made, and why?

It was an interesting set of experiments that we ran. The fundamental question at the time was, “Should we have subscription tiers that are more value-based and more user-based or tiers that are more features-based?” That’s maybe attention that other businesses may have as well. It’s not just specific to LinkedIn.

In our case, when I started, it was very user-focused. Who were you as a user? What were your goals? Therefore, what was the appropriate subscription for you as opposed to, “Here’s a list of features. You select the plan that maps to the features that you want.” That was what it was. We tried a version that was more features-based on this chooser page that had the four subscriptions and it didn’t work. It was one of my biggest failures during my time as a product manager and also one of the biggest learnings for me. That approach might have worked in a different business, but for the premium business at that time, it wasn’t right.

Product-Led Growth: We tried a version that was more features-based on this chooser page that had the four subscriptions and it didn’t work. It was one of my biggest failures during my time as a product manager and also one of the biggest learnings for me.

What did work?

We stuck with a bonafide version of the more user-based chooser. We continued to run experiments and make changes to how that selection process unfolded but didn’t change the fundamental premise that it was more based on users.

That is for people looking for a job or people in sales as opposed to people who need access to X or Y.

A certain number of INmail credits, for example, or one of that.

I appreciate you sharing that experience and also saying, “We tried something but it didn’t work.” I call this show True Tales from the Trenches, but a lot of times, people only share the stories that worked perfectly. Every good entrepreneur or business owner tries a lot of things. Some of them go well and some of them fail. Part of the success is being able to recognize, “This experiment didn’t work so I’m going to move forward with that new information with greater confidence.” I love that story.

I also like the way you broke it down between features-based and user profile-based, which is an issue that a lot of people have. You can disagree with me if you want, but the bias of most companies is to be features-based because that’s where they spend all their time. They’re understanding features, turning around and saying, “What are the different types of people coming to our site or looking to buy from us or subscribe with us? How are their needs different?” It is a different way.

That lens also helps you push yourself to say, “Are tiers even needed in the first place?” Sometimes, you can over-complicate your subscription lineup in a way that’s not helpful. If you hone in on what’s that reason for being, is it different use cases? Is it a different user audience or some other reason? You will be able to clearly articulate that differentiation versus falling into a feature-by-feature, “Let’s arbitrarily remove this feature from this particular bundle and then call it a new tier.” That is another lens as you’re constructing tiers.

It will not help you if you overcomplicate your subscription lineup. Clearly articulate what you want to provide to your user audience instead of trapping them feature by feature. - @caitlin_roman Share on XIt does seem to be an area that trips up a lot of people. When you ask them, “Why do you have that tier? Who is that tier for that is going to love that one and not the other one?” If they say something like, “It is somebody who wants more IN-mail credits,” it’s like, “I don’t know who that is.” You talked about how when you made that decision, you looked closely at the data. The data told you that it wasn’t working as well, so you moved back to making small incremental changes to improve the user-based approach or the user-based tiering.

You’ve told me before, metrics are not a set-and-forget-it thing. Rather, you talked about them as being something fluid and changing depending on the overall goals of the organization, the North Star metrics, the corporate metrics, but also the metrics of each specific team. People always say, “Which metrics should we focus on?” Tell me if I’m wrong, but I think the answer is it depends, and it depends even within the same organization over time.

The most important thing you can do as a product leader is to set the right goals, and that cascades down to the whole way the product team works. Think about Marty Cagan. I love the way he formulates his differentiation between feature teams and empowered product teams. The way you get empowered product teams is through good goals. That’s why goals are so important.

There are two layers to this. One is what the goals are at the top level of the company, and then the second layer is how you set up teams and orient them around goals that ladder up to that top-line goal. We’ll talk about the first. To simplify this a bit, in a subscription business, you can pretty much choose to focus on the number of subscribers or the average revenue you’re bringing in per subscriber. Often, these two metrics are in conflict. If you lower prices, you’re going to bring in more subscribers but you may not increase total revenue.

It’s important as an executive team to decide which metric, fundamentally, you want to grow at the end of the day. If you get the other two, that’s a bonus. That is great, but not assuming that you can grow both simultaneously. This decision has a big impact on the pricing initiatives you choose to pursue. To give an example here, at The Athletic, when we optimized for subscribers, we started offering a monthly subscription with the attractive introductory offer of $1 a month for 3, 6 or 12 months. This worked phenomenally well to drive subscribers, but it was not as great for revenue.

Down the road, we said, “Revenue is the top-line goal for the company. That meant we need to switch away from this monthly offer. We’re going to go back to annual that’s going to help us hit our revenue targets, but will have a negative impact on subscribers.” That’s a trade-off. As a growth product leader, you need to understand what the different levers are. If you change something, what’s going to be the impact on the other metric? Tee those trade-offs up so that you can help the executive team make these decisions. Once you make that decision, then the growth product team has a clear direction on what they need to do. If you’re waffling back and forth between the two, it can be disorienting for the team.

As a leader, my experience with a lot of executive teams has been, “We would like both. Can’t we have both?” What do you say when you’re pretty new to an organization and they say, “We would like both.”

That is a great question. It is a difficult one. Data is your friend here. Ideally, you have some sort of experiment that you’ve run that you can say, “We ran this experiment. It showed X for revenue and Y for subscriptions. This is the type of trade-off we can expect.” If you don’t have that data, which is entirely possible, it is trying to be calm about it and explaining the dynamics that you see, “We could do this thing and that would drive subscriptions.”

Do some back-of-the-envelope math and work with your analytics team. “I’m imagining, based on this set of assumptions, it might have this impact on revenue. Are we comfortable with that? What type of impact to revenue would we be comfortable with if we could get this amount?” You’re continuing to ask these different questions and framing them in different ways. Make certain assumptions and be clear about those assumptions. Have that back-and-forth dialogue in a rational way to help people start to think through and internalize that there might be these trade-offs.

For a lot of leadership teams, it is the way that subscription revenue comes in and the relationship between the way you acquire them. I imagine also at The Athletic, if you acquire somebody for $1 and then at some point, they go up to the regular rates, they might be more likely to cancel than somebody who came in at a full price. All of those nuanced details around how a subscription model works, you have to explain it. You have to look at the numbers and start to see how the pieces fit together.

I had one client. They were getting ready to fire their whole retention team because they were struggling to retain. It was a streaming company. The acquisition strategy was, “We have this one awesome title. Subscribe and get access to this one awesome title.” What would happen is people would sign up for the two-week free trial, watch the one awesome title, and then cancel either before they paid or in the first period.

That company saw that the retention team owned retention and the acquisition team owned acquisition. The acquisition team was doing a phenomenal job in their eyes, and the retention team was terrible. It is understanding that there is a correlation and that there are trade-offs, “Let’s acquire fewer people who are willing to pay the full price and they’ll stay longer. Maybe our lifetime value will be better, but we’ll have a smaller number of subscribers.” Those are trade-offs that often require education.

I could not agree more. It’s this open dialogue around how are the teams relating to each other. This gets into the second point around setting goals for teams that are cognizant of what other teams in the company are doing. You can’t set your retention team a goal of X percent retention if then on the acquisition side, you’re going in and acquiring unqualified users who are going to churn. The role of the growth product leader is to see all of these inter-relations and interdependencies, and articulate them to the executive team, as well as translate that into the goals for teams, which I can talk a little bit about now.

Product-Led Growth: The role of the growth product leader is to articulate interrelations and interdependencies to executive teams and translate them into business goals.

On this front, I believe in having a flexible model for team goals. We’re not setting and forgetting it. We’re revisiting those goals at least every six months, if not every quarter, through that quarterly planning process. For example, even if you have an acquisition team that remains stable over time, your strategy around acquisition may evolve as the business changes. In one quarter, it is like that example we talked about with Medium, it may make sense for that acquisition team to focus on driving account creation. In the next quarter, you’re focused back on driving subscriptions. That doesn’t mean that in that first quarter, you don’t care about subscriptions. It’s just that you’re focusing on the team so that their product work can be around driving whatever metric we think matters most strategically at this point in time.

It’s interesting. I like the focus and the discipline. It’s so much easier to build momentum when everybody’s working toward one shared goal than to have eight goals. There’s never a dashboard with one metric that tells you how the business is doing. Helping the team understand the trade-offs and giving them a focus point is wonderful.

There is something that I was curious about. We talked about having leadership teams that don’t know subscriptions, and trying to educate them about these trade-offs and relationships. I’ve seen a lot of mergers go badly when a subscription business is acquired for their multiple, but the acquiring company doesn’t know what to do with them when they get them. I’m guessing that was not the case when The New York Times acquired The Athletic being that both organizations are subscription-first businesses. Can you walk me through the experience of the merger of two subscriptions both as part of the leadership team at The Athletic and specifically as the functional head of the product team?

To caveat, I was there more during the period prior to the close of the acquisition, and then I left right after that acquisition closed. In terms of the transition, there are maybe two things to call out. One is as being responsible for the growth product team, we had certain growth targets that we wanted to hit that were very much relevant in light of strategic conversations that were going on. On the growth side, we wanted to be responsive to what was going on externally, but then at the same time, keep the team focused on the projects they were working on and not feel too much whiplash.

On the growth product side, it was that balance between responsiveness and keeping the team a little bit protected from what was going on in terms of external conversations. Similarly, if you think about being the functional lead of the whole product org, there is a lot of uncertainty when you’re in a strategic process like this. Certainly, once the acquisition was announced but it hadn’t closed yet, we were in this limbo period in terms of product planning. We were wanting to plan for 2022, but not knowing exactly what was going to happen once the acquisition closed.

For me, my goal was to keep product teams moving on projects that I had confidence would be of value in any scenario, and not let ourselves get bogged down in this limbo situation. There is a lot of behind-the-scenes work that happens among cross-functional leadership to engineering, design and analytics saying, “What are the no-regrets projects? How can we make them happen?” That’s where I spent a lot of time in the pre-closing phase. Post-close, The New York Times is best-in-class on the subscription front, so I don’t think there was any issue there.

You’ve been home for a little while since leaving The Athletic, being with your child and I’m sure, reflecting on what you want to do next. What are you thinking about?

I am excited to do something a little bit different perhaps in subscriptions or perhaps outside. I’m honestly pretty open. For those who have kids, you realize that you do this reset when your kid arrives very unexpectedly. When she came, I found myself excited to learn and stretch myself. I was perhaps inspired by the fact that she seems to learn something new every single day. I’m honestly pretty open. I’m looking to find a great company and a role where I can have an impact.

Are you up for doing a speed round to close our interview?

Yeah.

The first subscription you ever subscribed to.

The New York Times.

A product that you weren’t part of designing that you think is terrific?

What comes to mind is Figma, working with our design team and the big acquisition being on my mind right now. It’s a phenomenally design product for designers.

Your favorite subscription that you used this week.

I think it’s Stratechery. With a little bit more time, I’ve been able to read and stay more current with Stratechery. I often get behind. I’ve enjoyed being able to catch up and hear what Ben Thompson has to say about the tech world.

That’s a great subscription and a great source of information. If you have time to take a step back and read, it’s a great one. Thank you so much. This was a fantastic interview. It was chock full of tactical tips and also a broader perspective. I appreciate you taking the time to join us for this interview.

It was a lot of fun. Thanks for having me.

—

That was product leader Caitlin Roman who has led product teams at LinkedIn, Medium, and The Athletic. For more about Caitlin, you can follow her at Linkedin.com/in/CaitlinRoman. If you like this episode, please go over to Apple Podcasts or Apple iTunes and leave a review. Mention Caitlin in this episode if you especially enjoyed it. Reviews are how people find our show, and we appreciate each one. Thanks for your support. Thanks for tuning in to the show.

Important Links

- Caitlin Roman, Product Leader

- Medium

- The Athletic

- Acquisition of The Athletic by The New York Times

- Subscription Stories Episode with Jill Raines

- The New York Times

- Subscription Stories Episode with Greg Piechota

- Marty Cagan, Partner at Silicon Valley Product Group

- Sales Navigator

About Caitlin Roman

Caitlin Roman is a product leader with deep experience in subscription businesses. She got her start in subscriptions at LinkedIn, leading acquisition of Premium subscriptions. From there, she developed a growth product group at Medium focused on growing Medium Membership subscriptions. She then joined The Athletic in early 2020 to build a growth product team and helped grow that business to 1.2M subscribers prior to its acquisition by The New York Times in February 2022. Caitlin lives in Fairfax, CA, with her husband and 7-month-old daughter.

Caitlin Roman is a product leader with deep experience in subscription businesses. She got her start in subscriptions at LinkedIn, leading acquisition of Premium subscriptions. From there, she developed a growth product group at Medium focused on growing Medium Membership subscriptions. She then joined The Athletic in early 2020 to build a growth product team and helped grow that business to 1.2M subscribers prior to its acquisition by The New York Times in February 2022. Caitlin lives in Fairfax, CA, with her husband and 7-month-old daughter.

Love the show? Subscribe, rate, review, and share!

Join the Subscription Stories Community today:

- robbiekellmanbaxter.com

- Robbie Kellman Baxter on Instagram

- Subscription Stories: True Tales from the Trenches on Apple Podcasts

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]