Based in Germany, and a global leader in digital language learning, 16-year-old Babbel was part of the early wave of online subscriptions. When they launched, subscription pricing was unusual and controversial. The early team even had to develop their own Subscription Engine to support the business. My guest today, Julie Hansen, has led the company’s expansion to North America, as well as their evolving overall business strategy. In our conversation, we discuss the differences between European and US-Based Subscription best practices; how to make the case for investing in features that drive engagement, rather than just acquisition; and how a first mover can stay nimble even as the competitive landscape grows more crowded.

—

Listen to the podcast here

The 16-Year Evolution of a Global Subscription Pioneer with Babbel’s CRO and US CEO Julie Hansen

Based in Germany and a global leader in digital language learning, Babbel was part of the early wave of online subscriptions. When they launched, subscription pricing was unusual and controversial. The early team even had to develop their own subscription engine to support their business. My guest, Julie Hansen, has led the company’s expansion into North America as well as their overall business strategy. In our conversation, we discussed the differences between European and US-based best practices in subscription, how to make the case for investing in features that drive engagement rather than just acquisition, and how a first mover can stay nimble even as the competitive landscape grows more crowded.

—

Welcome to the show, Julie.

Thank you. I am glad to be here.

It’s great to have you. I want to jump right in with the Babbel origin story. Why did you launch with subscriptions, especially before subscriptions were all the rage everywhere?

It’s a great story. The company was started years ago when 1 of the 4 cofounders wanted to learn Spanish and turned to the internet and found there was no good way in Germany to learn Spanish online. These were four folks who were working together at another company. They broke off and created Babbel. They started out by creating the first product and putting it into the market. It was immediately a strong reception, but they decided that they were going to go for an ad-supported model.

After not very long, they saw that the advertisements were detracting from the learning experience. They were interrupting. They felt that was not the right model for an education product. We wanted to have a more sustainable model that would promote long-term customer relationships but would allow the best possible learning experience that didn’t have the interruptions of ads. That is how it all started. It was not a popular decision to go premium back then.

Who didn’t like that decision?

There’s a fantastic headline from Fast Company Magazine. The headline read Can “Freemium” Work? Babbel and WSJ Say No and One of Them is Wrong. It turns out that it was Fast Company that was wrong because that worked out pretty well for Wall Street Journal as well as Babbel. In general, the tech press didn’t like it. For consumers, it was a somewhat radical notion. We did not receive a lot of pushback at that time from the immediate consumer adoption of the model because the value was there and the user experience was what people thought was appropriate for a learning product.

Do you think most organizations that are teaching people something agree with you about advertising being disruptive to the learning experience? Is that an accepted truth?

It is, even for those organizations that still choose to offer a free model with advertising. There’s an understanding that that’s an interruption. Even if the ad is placed at the end of a lesson or what have you, it’s still a little bit of friction for the user to continue to the next lesson. One can argue that that’s an okay trade-off to have a free learning experience, so I don’t think that free will ever go away from learning products. It’s hard to argue that it’s hard enough to get people to do their homework. When you put a little friction between the user and that homework, it diminishes their success. You might have to overcome that with strong engagement features that might or might not work depending on the product.

I know you know that one of my first clients was Netflix, which is a streaming entertainment service. A lot of companies and I, myself, early on thought that whatever Netflix was doing was right for all subscriptions. The business model has to follow the content or the product being offered. Learning is different than being entertained. It’s a lean-forward, not a lean-back kind of experience. What have you learned about how people learn generally or specifically how they learn languages that have influenced how you design the user experience beyond no ads?

The user experience is critical in terms of creating an engaging and motivating learning environment. It is providing the right feedback loops, support, encouragement, challenge, and all of those. Getting the balance of those right in an app is super important. In language, in particular, there are a lot of proven learning techniques. There are quite a number of different learning philosophies or approaches, but we use the communicative method for the language nerds out there.

One thing that we’ve determined through a lot of research is that users need multiple touchpoints and they need guidance through their learning. Through multiple touchpoints, some of us learn better by reading or writing. I’m a writer. I keep a notebook of words. When I get a new word in German, I write it down. That’s how I remember. Others do better with listening or speaking. Most do best with all of those together.

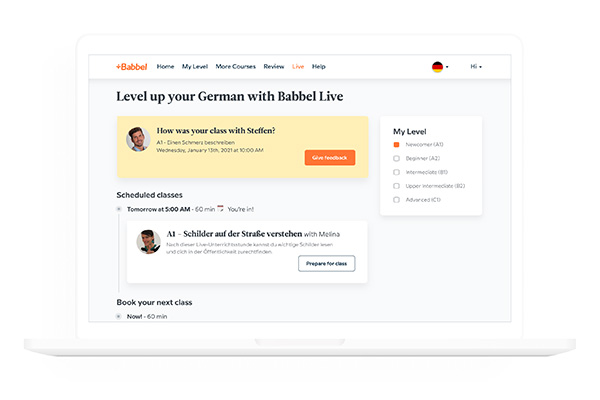

Over the years, part of what has made Babbel a great subscription product is we’ve been able to continue enhancing the product to bring more of those learning experiences to life in the product. We have video content, audio content, and culture bytes to give people an appreciation not just of the language but the culture of the people that speak that language.

We have a lot of fun games that we use to reinforce grammar or vocabulary. All of these things are brought together in the app. Some people respond better to certain learning methodologies, but they’re all there. That reinforcement or those multiple touchpoints is huge. At the same time, the notion of guidance is important to language learners in particular. If you and I tried to think back to when we were a year old learning a language, we don’t know how we do it. You do it as a child. As an adult, it’s different and confusing. There are a lot of different ways to go about it.

We are also very aware that an app will not make you fluent. Even Babbel will not make you fluent. We’re not suggesting it would. None of our marketing says that. What it can do is give you the perfect starting point and reinforcement, and that can get you pretty far. You need to enrich your learning experience with speaking and live classes, which we offer as a subscription product. The reason why we’ve gone deep into language rather than wide into other educational topics is we think that that’s the best language-learning solution. We are focused on the notion of efficacy. We want our solution to work. We want our learners to learn and to be able to go speak the language.

It’s interesting. I talk about this idea of a forever promise that a good subscription has a forever promise. It is, “You stick with us and we promise,” fill in the blank. For Babbel, it’s about, “We’ll help you learn the language,” as opposed to, “We’ll educate you on any number of topics. We’ll demonstrate the culture. We’ll help you plan a great trip,” or whatever other benefits you might have considered along the way. Was that an easy decision and an obvious decision or have there been temptations to expand broad and shallow rather than continuing to go deeper into language learning?

We have thought about which the right choice is for us. We have a technology that could be used in many different directions, but the company has decided that it’s better to be deep than wide and that language is our focus. I don’t know that when we started the subscription business, we had a well-defined notion of a forever promise. When you think about the journey, it’s exactly what we did, which is pretty cool.

We started out with a website. You can join the website, and then there was an app. You didn’t pay any extra for the app. The app came with, and there were podcasts. We have ten million downloads of the podcast. That is pretty rich support and enthusiasm for this new media. There is no extra money for that. With the games, you don’t pay extra for that. We kept adding more value to the product over the years. That’s exactly the point of the forever promise.

It’s a lesson that’s important. I hope people are taking the kind of discipline that you’ve exercised and how hard it is at the moment. Many businesses are focused on the new feature driving new subscribers or new customers and the idea of, “If we have a subscriber and they’re loyal, why would we spend more money to make it better for them? We already got them.”

I’m wondering. As you think about these new benefits that you’re incorporating into the subscription like podcasts and games in the cases where you’re not increasing the price, not the live piece but the ones that are incorporated as part of your standard offering, how do you measure or decide whether it’s worth investing in? Is there a metric that tells you, “It’s good that we did podcasts,” or, “We wasted a lot of money on that investment,” when it’s not directly tied to its own revenue line?

Two things are guiding metrics there. One is this notion of learner success. North Star metric is learner success, which is not easy to measure, but we do. We are always looking at new product enhancements in terms of whether they increased learner success and maybe any of the health metrics along the way. With usage and retention, did it help users get to a certain milestone in the product that we know is a trigger for learner success? That is always the number one. We then look at retention on the commercial side. Are people sticking around more? Those two work hand-in-hand, but one is the most important, and that is the notion of learner success.

When you introduce a new benefit or a new feature, you’re tying that to, “How do we measure the impact of that new feature on learner’s success and, to a lesser extent, retention?” which can be a proxy for whether or not they’re having success, they believe they’re having success. They’re sticking around. They’re feeling good about it. Even if we can’t prove anything, they feel like it’s worth their time.

That’s an important challenge for a lot of organizations, thinking, “When do we add features? How do we prove that those features are worthwhile if they’re not driving acquisition?” I often talk about how you have features that drive acquisition and features that drive engagement and retention. You have to know what you’re trying to do and what you’re optimizing around before you add a feature so that you can tell if it works or not. It’s different than having 25 different products that are all transactional and letting the market tell you, “More people are buying this and fewer people are buying that.”

We’ve made the deliberate choice to keep enhancing the core Babbel product as opposed to launching lots of different products. For games, it is not a separate app. It’s part of Babbel for that exact reason. We believe that if users achieve success, they are making progress. If they are able to speak or if they take that trip and they can order in the cafe, and all of those things, then they’re happy to pay. If they’re not using the product and not learning, then they should cancel. We don’t want to make that hard either. It’s about the user’s success.

Can I quote you on that? That’s a bold and confident statement from a leader. I love it.

We have always had a twenty-day money-back guarantee as well. Some people take us up on that. There’s no fight. It’s important. We once had a very, for me, fun discussion at the executive level about, “What do we think about those users who have a subscription and it’s renewing, but they’re not using the product?”

At the time, reflecting on the US experience where we have so many aspirational learners but less opportunity to use a new language in this country, I said, “Maybe it’s like a gym membership or a membership to that high-brow literary publication that sits on your coffee table. You don’t get to read it every week, but you want to have that subscription because you want it there when you can. You aspire to it. Is that good enough for us? From a user perspective, that’s meeting a need.” Everyone thought about it and was like, “No. We want them to learn.” It’s a strongly held view in the company.

That’s great. There are a lot of people that go with the aspirational model and say, “We’re giving people hope, whether that is hope that they’ll lose weight, hope that they’ll go to the gym, or hope that they’ll read The New Yorker instead of Netflix and chill.” There are lots of aspirations in subscription products, but at the end of the day, people feel best about the products that they use.

Netflix has led the way by saying, “If you haven’t used your product or you haven’t logged in in a year,” which, granted, is a very long time to be paying for something and not using it, “We’re canceling you. We’re kicking you out because we don’t want your money.” Granted, it’s still twelve months, but the idea is the right idea.

You want people to get the value they came for and get the outcomes they came for. That’s the best metric. The second best metric is are they using the product? Do they believe that the product is helping them on that journey? These are important points. I appreciate what you said about that. You’ve brought up a couple of times the fact that the Babbel is located and based in Germany. You are in the US as a very big business, but it does have strong German roots. Are there cultural differences especially in how they think about a subscription?

For sure. I started several years ago in the US business and I run global revenue, so B2B and B2C. I’m working with the Berlin-based team all the time, which has given me an even deeper appreciation of cultural differences. Within the company, we have employees from more than 70 countries. It is an amazing experience to work with so many cultures under one roof.

You could argue that our German roots provide a focus on quality, reliability, and innovation. We’re the quiet improvers rather than the flashy tech newcomers. We do not overpromise, and those might be classically German traits. These cultural differences are real. They can be very challenging, but they can also provide amazing opportunities for learning and growth. I’ve learned a lot about abstraction, planning, and process by being a part of this company. I’ve probably shared, in return, urgency, pragmatism, and optimism, which are classic American traits.

It’s not just German and American. There are 70 nationalities. Babbel launched in Germany and then grew quickly in Europe. It was an overnight success. The Babbel brand in Germany is a household name. You get in the taxi and they know Babbel. That’s amazing. I love to tell Americans our first marketing slogan because it inevitably draws a good laugh. It was, “You could learn a language online.” You’re thinking, “Who cares? Why do I care? Do I even want to learn a language?” It is such a different starting place.

When we got going here, we had to change the messaging because the motivations are so different. We also changed the media mix pretty radically. The US, from a media perspective, we are a crystal ball. What happens here will happen in England in about 2-and-a-half years in the UK and then in Germany in about 4 or 5 years. Why would we be looking backward to the media environment? We should be looking forward. We leaned heavily into social, digital, podcasts, newsletters, and all the things that took off over the past couple of years in the US market. We had to change everything.

We also had to change even the products a little bit to make them more culturally relevant. The number one complaint to customer service when I started in the US was that we had the wrong Spanish. We had the Spanish that they speak in Spain. The US learners don’t learn that anymore in school. It’s Mexican Spanish, so we had to bring that out. We then added more podcasts because that’s of interest to the US audience. Even before Germany, we made the lesson shorter. There are quite a number of cultural differences that have an impact on the product itself and the marketing.

In terms of the willingness to pay for a subscription, that is pretty universal across the two continents or worldwide. Maybe in certain Latin American countries where credit cards aren’t as commonly used, it’s a slightly different attitude. We’re going to try on different models there. We don’t see much difference in the US and Germany or elsewhere in terms of acceptance of subscriptions.

We don't see much difference in the US and Germany or elsewhere in terms of acceptance of subscriptions. – @julie_hansen Share on XThat’s interesting. I have several clients that are expanding globally in different ways in different regions. They are asking questions like, “Does China accept subscriptions?” It feels like a pretty monolithic or overly simplistic question, but that is a question that one client asked. One was like, “Is it too early to take our products,” which you’re doing very well in the US, “to the UK?” What advice do you have for your North American peers that are looking at the rest of the world as having been on the journey from the other direction?

I know the most about European expansion. There, you have to pay a surprising amount of attention to pricing. It’s not one price for all of Europe. You have to pay attention to make sure that your GDPR stuff or your privacy stuff is in order. It will be an evaluation point for a certain number of European buyers. It’s not the fine print the way it might be in the States. It’s important to be upfront about that. You’ve also got to localize the messaging.

You have to pay a surprising amount of attention to pricing. It's not one price for all of Europe. – @julie_hansen Share on XIt is localizing the messaging and understanding both the regulations by market and also how those regulations are perceived by consumers. You talked about the pricing sensitivities. I’m assuming that you mean that different markets have different abilities to pay, so the price as a percentage of their income or as a percentage of the discretionary income is very different.

We’ve found fascinating differences. In the US, you would often see three pricing cards, and the one in the middle is just right. In Germany, we give them five prices. They want the data, so we give them more options. In the US, that would be considered overwhelming and bad practice, but it has often worked well for us in Germany. You’d never know that until you had German colleagues who suggest we try it. It’s amazing. There are certain markets in Europe where, frankly, if you raise the price, you might increase sales because it would be perceived as a marker of quality. In other countries, you will crush sales if you raise the price too much. It varies a lot.

Language Learning: In Germany, you can give customers several prices so they can have more options. In the US, that would be considered overwhelming and bad practice.

Do you have to learn it from your peers and the school of hard knocks, or is there some cheat sheet, book, or insight that helped you understand all of these interesting market dynamics by country or by region? Even the example of Germans wanting to see 5 options whereas Americans wanting to see 5 options is really interesting to me.

We have people. That’s our secret. We have people in the market. It’s the reason why my role exists and the team of 70 people that we have here. We needed local experts. That’s part of the magic of having the 70 different nationalities in the Berlin office. We can always ask the French person, the Spanish person, or what have you.

Language Learning: Part of the magic is having the 70 different nationalities in the Berlin office.

There’s no substitute for peers who are helpful. It’s interesting. One of my past guests was the CEO of Tinder. She had grown up Apple, managing European apps or expansion from the US into European countries or European apps that want to reach out to the US market. She said some very similar things. She said, “Localizing is more than changing the language. It’s about everything including the offer and this importance of getting into the nuance of each country and each region because they don’t all play like the US.”

It’s like the Netflix example. You can learn a lot from Netflix about subscriptions, but not every decision that Netflix makes can be applied to every other kind of business. The United States does a lot of things really well and first in subscriptions, but you can’t just take the US playbook and apply it to other markets without considering those nuances.

I 100% agree. There are interesting nuances around how much email is too much email. We have a certain email cadence that we send out to our leads and even our subscribers here in the US. It’s normal. That works. Our European colleagues feel strongly like, “We cannot send that. Many people will unsubscribe. It is bad.”

That’s an easy one to test. I have a very nice client from Canada. Canadians are known for their friendly, gentle, and polite ways. I was talking to them about, “You could be a little more direct in your messaging.” We had to talk about it, and they were like, “We feel like that’s a lot.” That’s easy to test. You send out a message with a stronger tone, and either people unsubscribe or they don’t.

I know some companies. They test even here, “What would happen if we sent out one message a week?” I would be like, “That seems like so much.” They’d be like, “What about if it was once a day? What about if we had a morning, mid-day, and evening?” Especially in the world of news, they are like, “What if we had a newsletter for each subtopic?” You push the envelope and have some number in mind that this churn kind of is okay. You find out that these ideas about different levels of email by country are true.

We are starting to test that theory. I agree with you. That is testable. We’ll see. My prediction is it will be somewhere in the middle. Maybe the US quantity and cadence of emails will be too much, but probably what we’re doing is not enough.

That’s always a challenge. The benefit of having leadership from another market or another industry, frankly, is that they can look at things and say, “You’re not special. This should work.” For example, for many years, law firms and venture firms had a belief that marketing was cheesy, full-stop. Having a beautiful website and keeping it updated would be perceived by the market as being a non-serious firm. We know that’s not true. Companies like McKinsey or big venture firms spend a fortune on marketing. It’s interesting to balance between, “We know our audience,” or, “We know our people,” versus, “This is how we’ve always done it. We’ve never tested it.” Those are interesting questions around this European-US question.

You mentioned that early on, in Germany, you were the first language app or the only language app. You were the beloved local darling or favorite monopoly. Certainly, here in the United States, you’re seeing more competitors. This is a good space. Language learning is important. Lots of people want to do it. There’s Rosetta Stone, which has mostly used an ownership model where you buy the software and then you own it. There’s Duolingo, which is mostly free. I’m curious. As you see a more crowded market, how do you change or not change your strategy?

We live a Harvard Business School case study each and every day because we are in a market with very different business models. That’s super interesting. The other thing that business school would remind us of is that competition is good. You need competitive forces to make your best product, do your best marketing, etc. It’s good that there’s competition.

You need competitive forces to make your best product, do your best marketing, etc. It's good that there's competition. – @julie_hansen Share on XThe pandemic boosted pretty much all players in the market. The leaders have continued growing. That says something about the power of more than one market player to grow the market, which probably wouldn’t happen if we were a monopolist. We would still be able to sleep at night, being a monopolist. It would be okay, but we don’t have that luxury anymore, not in the English-speaking world or the Spanish-speaking world in particular. It’s good to have competition.

Because we started so early on with this premium model, that’s what has defined and distinguished us. We are all about the high-quality learning experience, the blend of humans in technology. Staying focused on that space, deepening the content that’s available, enriching the product, and hammering on the efficacy is what this strong competition has forced us to focus on and be clear about how Babbel is different and better. That’s also a good thing.

It’s interesting. For people reading, being the monopoly is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, you have no competition and you can own the market. On the other hand, you don’t have anybody making you better. You don’t have anyone else footing the bill for educating the market that this is an offering. If nobody else wants to play, there might be a reason for that. Maybe you’ve got some big barriers to entry, but it may also be that there’s not as much potential as you thought. A lot of times, having other players supports the growth of the whole space and the confidence in that space.

Yes, 100%. Monopolists do tend to be vulnerable to blind spots as well. Good competition helps to shield you from that.

Good competition helps you see that there are other ways to do it and other ways that work. There are other kinds of segments that are interested in a free product and they don’t mind the ad interruptions. Some might want to pay one time and never have to pay again. There is some subscription fatigue out in the world.

When I wrote my first book, The Membership Economy, I believed that a company had to commit to subscription pricing. Either you were a subscription business like Netflix or you weren’t. I saw, for example, Hulu or when I worked with newspapers that have a lot of revenue from advertising but also have circulation revenue or reader revenue think, “This is hard. It’s too many different models.” Not only is it distracting for the marketing team that’s trying to sell these products, but it’s distracting for the product team. Designing an ad-driven product is different than designing a product that somebody paid for upfront.

Over the years, I’ve changed my tune. I still think it’s more expensive and it’s harder to have multiple models, but I understand how it can expand your reach that sometimes, one model leads to the other. The freemium ad-supported model gives people a chance to taste your content, then when they decide that they believe in what you’re doing, they can upgrade. What do you think about offering multiple types of packaging for your value? Is that something that you think about? Where do you come out on that as you see your peers doing other things?

We’re very excited about the possibilities that mixed models open up. Subscriptions will always remain a core thing that we offer. This is because we love the way it aligns our goals and our consumer’s goals. We keep improving the product, and they keep improving their learning. That alignment is fantastic. The one-time payment options offer up so many possibilities, especially for a company like ours with more products that we’re bringing to market.

Subscriptions will always remain a core thing that we offer, because we love the way it aligns our goals and our consumer's goals. – @julie_hansen Share on XTo give you some use case examples, imagine a consumer who’s not ready to commit to live classes yet or not ready to sign up for a schedule but wants to add a couple of live classes a month to her app subscription so that she can practice speaking. We can’t do that now, but we’re soon launching a new billing management system that would allow that. That’s a great use case.

Our core market is lifelong learners. This is not a classroom product. It’s for people, adults mostly, who want to learn. If you’re a lifelong learner, a lifetime subscription is a pretty nice option. With a one-time payment, you use it forever. You know that language learning can be a lifelong pursuit. It’s not an overnight thing. This lines up well for a lot of people.

Language Learning: Language learning can be a lifelong pursuit. It cannot be accomplished overnight.

Such a common American use case is the family planning their European vacation. They have a fixed-term need. They’re getting ready for a trip, so a one-time payment family pack is ideal for them. When they come home and they want to keep going because they fell in love with the language, then they can upgrade to a subscription. There are a lot of use cases where either one-time payments or a mixed model is powerful.

I think about your forever promise around the best way to get started in learning a language or the best way to learn a language. I’m then thinking if that’s true, the best way to learn a language for a family going to Europe might be different than the best way to learn a language for someone who married a non-English speaker from another language. If you want to learn to speak with the in-laws, childhood friends, and all of that, you might have a longer runway than if you’re optimizing for Europe.

Also, your example of maybe I’ll take a few live classes, I’m probably more likely to take the live classes right before my visit, whether that’s my European trip or my first visit to meet my in-laws. Afterward, the stakes are a lot lower. Maybe I go back to the online-only or I go back to once a week checking in with my language learning as opposed to dedicating time every day. I find that interesting, the expansion over the years of who you’re serving and where you’re investing more to serve them better.

I want to touch on this point because it’s important. You’ve been around for years. You brought up the point that your new billing system is going to allow you to offer these different pricing options. For many people reading, they have lots of ideas of things that they would do, but they are limited by their platform. Maybe because it was self-created. Maybe because it’s old and it was bought when they had a different idea of what their model was going to be. They’re trying to make it work. They’re jerry-rigging it together but it’s not optimized for their vision for the future. As a business that’s been around for years, how have you thought about the technology to support your strategy?

Several years ago, we had to build this. There were not a lot of options out there. We built something that worked great for a decade and a half. It’s stable. It’s efficient. It works. It got the job done. It allowed us to focus our energy on the product, not necessarily on the commercial side of the technology. The time has come for us to re-examine that decision because we’re entering a multi-product world. That creates far more complexity in how you sell what you sell.

Language Learning: Babbel built something that worked great for a decade and a half. The time has come for them to re-examine it as we enter a multi-product world.

We’ve jerry-rigged and hacked about as much as one might want to. For example, do you want to give Babbel as a gift? That’s great. You can do it on our platform. It’s time for us. We waited long enough that we have a good understanding of what is missing and what we need. It’s a non-trivial decision. These are big tech projects that come with hefty bills, but it’s time for us.

Your point about you know what you need, a lot of companies don’t even know what the requirements should be. When you hear a pitch from a vendor, they all sound good. The hard part is saying, “These are the actual things we need to do. Can you do that?” Having that requirements document is so important.

Many of those requirements have come out of things we’ve learned the hard way. I’ll put it that way.

It’s so interesting. You’re going to get something really good because you know what you need at this point. I could talk to you all day. I have a lot more questions. I want to close out this interview with a speed round if you’re up for it. Answer with the first thing to pop into your head. Are you ready?

I’m ready.

What was the first subscription you ever had?

It was a teenage girl magazine back in the day. I’m dating myself here. I know, but I’m pretty sure it was either that or Sleek Magazine.

What is your most favorite subscription?

It is Strava besides Babbel.

I do have a nice interview with the Chief Revenue Officer at Strava if people are interested in learning more about how they think about their subscriptions.

Talk about continuing to add value, more features, and more products. They do a great job of telling the users when they do. I am a huge fan.

I will share that. That’s great. What is something you can say in three languages?

Thank you. Merci. Danke.

What is the last course you took in any subject besides language?

It probably has to go with a sports theme again, learning how to ski. I took some classes. I clearly did not take enough because I broke my leg. That’s probably the most recent one that I took.

The last question is do you have advice for other first movers facing an increasingly crowded landscape?

Keep your time horizon for strategy short and long. Make sure you’re looking far enough around the corner to spot those long-term trends but also reviewing it and revising it every year. Focusing on incremental improvements is so important. It might be old-fashioned or out of flavor, but I also appreciated Andy Grove’s Only the Paranoid Survive. There is something to that. We live in a very competitive world. That was probably three pieces of advice, but there you are.

It’s great. I love that. Use your microscope and your telescope. Be a little bit paranoid. That’s a great place to end. Thank you so much for being our guest. It was a real pleasure.

Thanks. It was fun.

—

That was Julie Hansen, Chief Revenue Officer and US CEO of Babbel. For more about Julie and Babbel, go to Babbel.com. If you like what you read, please go over to Apple Podcasts or Apple iTunes and leave a review. Mention Julie in this episode if you especially enjoyed it. Reviews are how the audience finds our show, and we appreciate each one. Thank you for your support, and thanks for reading.

Important Links

- Julie Hansen, Chief Revenue Officer and US CEO, Babbel

- Babbel

- Article on Can “Freemium” Work? Babbel and WSJ Say No and One of Them Is Wrong

- Rosetta Stone

- Duolingo

- The Membership Economy

- Subscription Stories Episode 29: How Strava Built a Subscription Business within a Social Platform with David Lorsch, CRO of Strava

- Subscription Stories Episode 20: Tinder’s Renate Nyborg on Going Global with Your Subscription Model Only the Paranoid Survive

- Only the Paranoid Survive

About Julie Hansen

Julie Hansen, CRO and US CEO of Babbel, is focused on accelerating Babbel’s global growth and transforming Babbel’s successful language learning app into the leading online language learning platform, offering various learning experiences for consumers and businesses alike.

Julie Hansen, CRO and US CEO of Babbel, is focused on accelerating Babbel’s global growth and transforming Babbel’s successful language learning app into the leading online language learning platform, offering various learning experiences for consumers and businesses alike.

With a proven track record for growing digital companies, Julie’s experience spans more than two decades and multiple sectors including growing digital media companies, launching interactive websites, deploying mobile apps, and leading online and offline marketing campaigns. Before joining Babbel, Julie was the COO and President of Business Insider. Under her leadership, the digital publication became the most visited business outlet on the internet.

Her experience includes holding top management roles at CBS Sports and Condé Nast, relaunching NCAA.com and leading the digitalization of titles like NewYorker.com and TeenVogue.com. Her unique media background and clear business acumen bring a fresh perspective to Babbel, turning the company into a content and innovation powerhouse.

During her time at Babbel, Julie’s leadership has resulted in immense growth in the U.S. for the Berlin-based company. In the first half of 2022, Julie led the company to sell more than 1 million subscriptions in the U.S. alone, making it the company’s largest and fastest-growing market. She also helped launch Babbel for Business in the U.S., which offers language learning as a part of a company’s professional development program.

Love the show? Subscribe, rate, review, and share!

Join the Subscription Stories Community today: